Many are worried about side-effects, and that clinical trials have been conducted too quickly

After months of dark headlines about the coronavirus pandemic, at last there is hope on the horizon. Last week Pfizer and BioNTech, two pharmaceutical firms, unveiled early data showing that their experimental vaccine is 90% effective in preventing covid-19. On November 16th Moderna, another pharma company, reported that its jab is nearly 95% effective. Financial markets cheered: on both days the S&P 500, America’s main stockmarket index, set record highs. More vaccines are probably on the way.

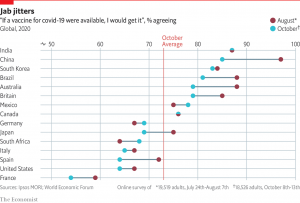

But there are still hurdles to overcome. Both vaccines must undergo further testing. Vaccines have to be manufactured in huge quantities and distributed effectively. And people must be willing to have the jabs. This may prove surprisingly problematic. According to a recent poll by Ipsos-MORI, less than three-quarters of adults say they are keen to get vaccinated for covid-19. The poll, which was conducted between October 8th and October 13th, asked 18,000 adults in 15 countries whether they would get a vaccine. Just 73% said they would, down from 77% in August. Only in three countries—Mexico, Germany, and South Africa—were people more eager to get vaccinated in October than they had been two months earlier. France remained the most reluctant country overall (see chart).

Why the hesitation? The most commonly cited reason was worry about side effects (34%), followed by concerns that clinical trials had moved too quickly (33%). Around one in ten respondents said they are against vaccines altogether. But such “anti-vax” sentiment is not common. Respondents were more likely to say they would get the vaccine, but not right away. Indeed just 52% said they would accept one within the first three months of its availability; 12% said they would wait at least a year to get inoculated. Some demographic groups are especially suspicious: those with less education in Australia; those on lower incomes in France; and the unemployed and African-Americans in the United States.

Such scepticism could prolong the pandemic, and it is worrying that it appeared to be mounting in the autumn—perhaps because of suspicions that vaccines were being rushed through. Public-health authorities will hope that this week’s news might reverse that trend. Most models suggest that, even if the vaccines under development prove highly effective at preventing covid-19, at least two-thirds of the population will have to be vaccinated to quash future outbreaks. Failure to address the public’s fears soon could disrupt even the best-laid plans.

Most models suggest that, even if the vaccines under development prove highly effective at preventing covid-19, at least two-thirds of the population will have to be vaccinated to quash future outbreaks. Failure to address the public’s fears soon could disrupt even the best-laid plans.